Eric Li on becoming a design founder through intentional career exploration

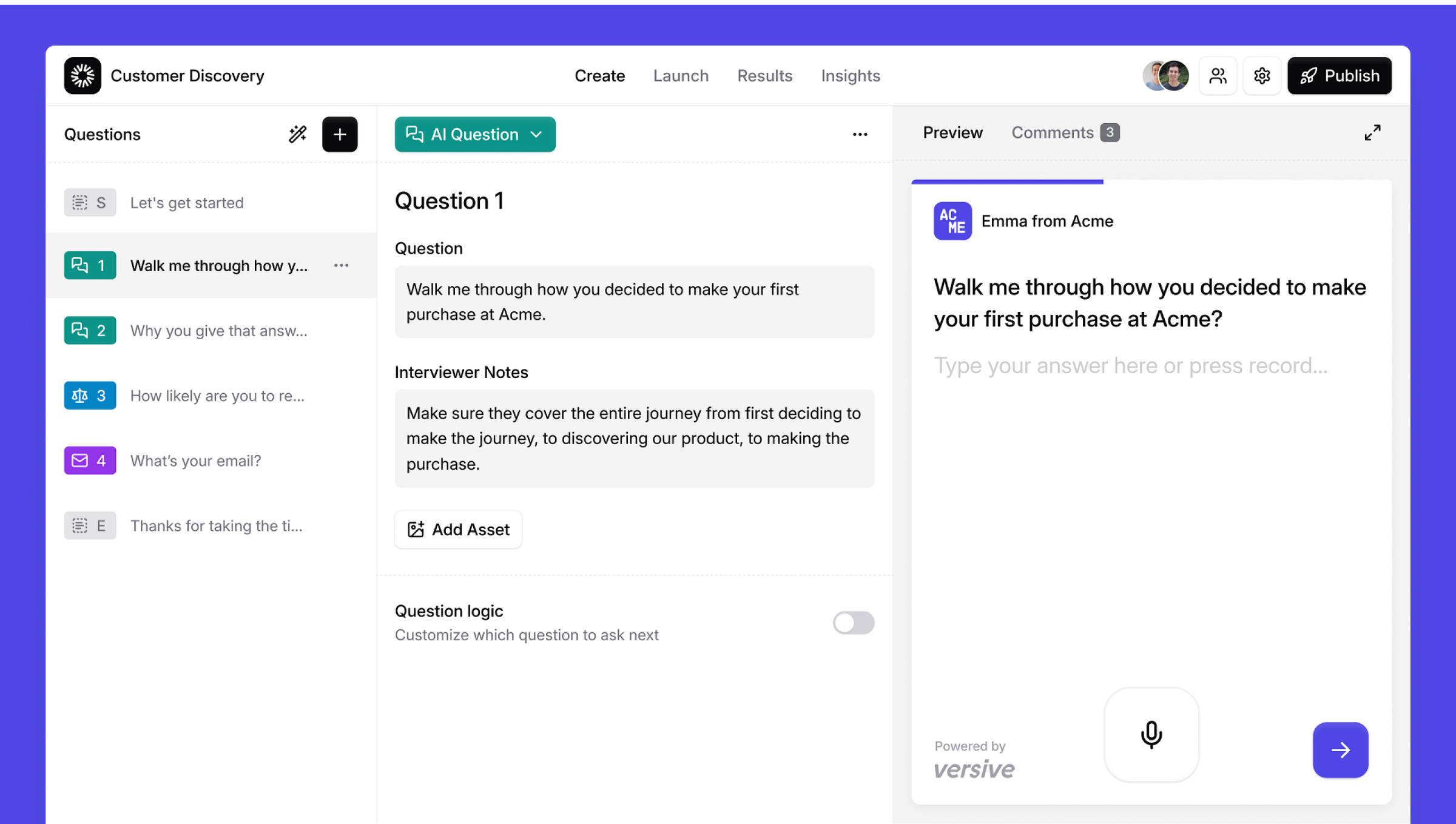

Meet Eric Li, co-founder of Versive, an AI-powered user research platform that helps companies conduct and analyze research faster.

Meet Eric Li, co-founder of Versive, an AI-powered user research platform that helps companies conduct and analyze research faster. Eric started his career in finance, transitioned to design, tried out product management, and eventually founded his own company. He shares with us how he approached exploring new careers, building new skills, and what he learned along the way in each role through the lens of solving creative problems for people by building for them and their needs.

Interviewed on March 2024 | This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Tell us a little about yourself—who you are and what you want the audience to know. I'm Eric, co-founder of Versive. We're a user research tool that uses AI to help people conduct and analyze research faster.

As far as careers go, I've gone through a lot of different twists and turns. I started working in investment banking and then pivoted into becoming a designer, with some stints as a product manager in between. Then, ultimately started Versive, which also had its twists and turns.

I grew up in the Chicago suburbs. I've been in New York for over ten years and live in Brooklyn with my wife, Emily, and my cat, Mochi.

Let's start at the beginning of those twists and turns. Could you share how you started in finance and where design came from? In high school, I did all the school stuff I was “supposed to” but was also interested in art and painting, which I always thought of as a hobby. But I really enjoyed it; it was a small part of my identity. When I went to college at the University of Chicago, there was almost no trace of any design program [at the time]. I met some friends who were also interested in art and design. We knew people starting nonprofits, student organizations, and companies, and no one knew anything about design. People needed to create logos, marketing materials, and websites. There was a problem people needed to solve, which seemed interesting, so I decided to try to solve it for people.

But then, I also spent a lot of time trying to get good grades in my econ classes and joining business-related clubs. In junior year, everyone started recruiting for investment banking and consulting jobs. I realized this is the game everyone plays, so I decided to play as well and see if I could get a good job at the top firm. I did it because I didn't know what else to do, and it seemed like a safe path. If I were to go back in time, I wouldn't have done that [route].

Why not? It was less, "I'm super passionate about this," but more, "This is a thing that is good for me, and if I do it, I'll have a good career, and people will be happy with me." While it was interesting, I liked solving more creative problems but didn't know I could make a career out of it.

What happened as you went from designing for fun to pursuing a career in finance? What did you end up doing, and what were some of your learnings? My ultimate goal was to get a job in investment banking. I did an internship that turned into a full-time offer with JP Morgan in their Tech, Media & Telecom investment banking group in New York.

Typically, you're supposed to work in banking for two to three years. Then, most people will go into a private equity or corporate finance job at a big company. I ended up staying for only a year and a half—up to my first bonus.

Overall, it was a good experience. I made some good friends because you're working in your little cubicle with other people who just graduated from college. You're there for 80-100 hours a week, and you see these people more than anyone else.

I also learned how pointless a job can feel and how many hours you can still put into it. Maybe I also improved my work ethic. After having [worked in investment banking], every job after seems much more chill, especially after moving to tech.

What factors did you consider to help you decide to move out of finance? Investment banking is a job that provides services to other businesses. Most of the job involves pitching and selling to companies to "Use us to do your M&A or raise money." You're trying to sell the customer what they want to hear and help them facilitate the transaction. It adds some value, but that wasn't what I wanted to do. I wanted to find a job where I was actually building something for people and solving their problems.

So I didn't like the job I had, but I also didn’t like the job I would have next. In investment banking, you start recruiting for your next job after six or seven months when you barely know your current job. If you get an offer, you basically work in banking for another year and a half before starting the next job. I did exactly that and got a job at a pretty good private equity firm. I went to their welcome event, and everyone was making jokes about how they hated the job. And I'm like, "I don't know if I want to do this either."

Most importantly, I was in a long-distance relationship with my girlfriend, now my wife, who was still in Chicago. I wanted to be in person with her. I had this job that I didn't really care about, and I wondered if there was a way I could quit my job and move to Chicago.

Out of nowhere, an opportunity fell in my lap. I had a friend who ran the product and analytics team at Sears, the big retail company, and he was hiring for a role on their strategy team in Chicago. I interviewed with them and decided to take the position, quit my job, and move to Chicago. It was all very quick and impulsive, but it was also a very clear-cut decision.

What happened next? Working at Sears was fun, chaotic, challenging, and frustrating all at once. It also led me to discover that I wanted to become a product designer.

In my new role, I started as an internal consultant working with different teams to use data and new products to grow our loyalty programs and encourage customers to spend more money with Sears. My boss was a 20-something Senior Vice President (SVP) who reported directly to the CEO, a hedge fund manager who bought Sears and merged it with Kmart. It was a weird situation because I knew nothing, and I was supposed to tell all these people who had been working at Sears for 20-30 years what to do, give them advice, and work with them on projects.

Our CEO wanted to do a lot of product experimentation with social commerce and our loyalty programs. He acquired a company in Israel that was trying to build a social shopping website. I flew to Tel Aviv every month to work with them and got my first exposure to the world of product managers, designers, and engineers. Eventually, my boss let me build my own team focused on launching 0 to 1 products for our loyalty program. Looking back now, I was not very good at my job, but I learned a ton.

I especially loved working with designers. Product design was the perfect combination of my creative and logical sides. I loved that it combined visual design, problem-solving, and business strategy. This was the moment I realized, "I want to be a designer."

How did you make the move into design? I wanted to get a design job outside of Sears at a more tech-centric company. I started applying to jobs but heard back from almost none of them. When you don't have real experience and are trying to get your first job, it's really hard to get your foot in the door.

I started reading design newsletters and listening to podcasts to try to better understand the industry. I also figured I would need to build a portfolio of work, so I tried two things.

First, I started making design a bigger part of my job since our team was short on designers. I started not only writing product requirements but also creating mockups—first building wireframes in PowerPoint before eventually using Sketch to design full high-fidelity flows.

Second, I started working on a creative project with my friend, Alex. When we traveled for work and fun, we were inspired by the cool local fabrics we saw at markets around the world. So, we started a fashion brand where we made men’s button-down shirts out of interesting fabrics that we found in Japan. While it never became a real business, we sold tens of thousands of dollars of shirts, and I designed and built a website that made it into my portfolio.

With a scrappy portfolio of real projects, I applied to many more jobs and got a few interviews, leading to two or three final rounds. I ultimately landed a job at a small startup called Capture, building products to help companies like CNN and Buzzfeed search for real-time social content on platforms like Instagram and Twitter. The team liked my work and took a chance on me, and I’m still grateful for the opportunity.

I became the only designer in a 5-10-person company, working closely with the CEO and engineers in a small office in Soho—it was a great experience. We didn't follow the “proper” design processes or do a lot of research, but we shipped a ton of work. I only worked there for 6-7 months before we were acquired, but during that time, we redesigned the entire app and designed a brand-new product, which was great for learning.

So what happened after Capture? When we were acquired, it wasn’t a meaningful outcome for me as an employee, and I didn't want to join the acquirer, so I started looking to join a better-funded startup where I felt like I could grow with the company. After interviewing at a few companies, I landed at Bread, a small startup that helped retailers offer pay-over-time plans to their customers. I joined as the first designer when the company was less than 20 people, and it grew to around 200 while I was there.

It was really cool to see a startup grow and become a real business. I grew a lot as a designer there, shipping lots of new features, leading a rebrand, helping to hire product managers and designers, and setting up our first research processes.

Bread was also a great training ground for my current role as a founder. The cool thing about being at an early-stage startup is that you get to see everything. For example, you're talking directly with salespeople, sitting right next to your engineers, and overhearing the customer support calls. You're also not bound by your job description. I set up our product analytics, wrote the front-end code for our dashboard redesign, and helped put together our fundraising decks. My experience at Bread was a preview of what I'm doing now as a founder. It’s not the same as being responsible for everything, but it was probably one of the best ways to learn.

Oh, and I also got to work with some fantastic people, including my current co-founder, David, who was one of the first engineers.

My experience at Bread was a preview of what I'm doing now as a founder. It’s not the same as being responsible for everything, but it was probably one of the best ways to learn.

Since college, you've always had something tangentially related going on in your path. During this stage of focusing on your design career, did you also focus on something else? No, I don't think so. This was a period where I was very satisfied. I liked my job and was still being challenged. I also found fulfillment in my personal life. I got married to my wife Emily when I was at Bread.

So you transitioned from a small company to a large one and transitioned out of that after. What spurred that decision? I really enjoyed working for a startup, but I still wanted to work at a top company, one that was known for design. At Capture and Bread, I was good at my job but part of me always wondered if I was a good designer. Maybe it was because I was self-taught and never had a design education, but I wanted to work with other designers and get some validation so I would be able to say, "I know what I'm doing"

After Bread, I was lucky enough to get a job at Uber. Uber Eats was actually the top company I wanted to work at. I remember reading a blog post about how the team did research around the world, and I thought, "Oh, that's so cool.” It's like you're designing not only an app but also the real-world interactions.

My number one takeaway at Uber was that it’s a lot of fun to work in a team with other designers who all understand each other. I made some good friends and worked with some talented people. The second was that the work itself wasn’t that different from my time at Bread, but you end up spending more time on things other than design. There’s a bigger focus on process and building consensus, but I felt like I could get good at it if I put in the time. Still, it was a little frustrating to be moving so slowly and needing to spend so much time advocating for projects and being okay with your team’s ideas not always being implemented. I definitely worked on some projects that didn’t ship until a year or two after I left the company.

There are pros and cons to working at a big company, but it was also really cool to work on something at scale and ship experiences to hundreds of thousands or millions of people and see whether they work.

What drew you back to a smaller startup after your time at a big company? The first year at Uber was great. The company was growing, and the world was very happy in 2019. We got to do a lot of traveling for some really interesting research projects.

But then Covid hit and everyone started working from home and the company went through layoffs. Luckily, I wasn’t affected, but it made me reevaluate what I wanted in my job. I missed the autonomy and ownership I had at Bread and Capture and I wanted fewer Zoom meetings and more doing.

I wanted to start my own company, but I wasn’t sure if I was ready to do it right away. I didn’t have a compelling idea, and there wasn't someone I wanted to work with. So, I decided to find a very early-stage startup to see if I could get paid to help someone else build a product from scratch.

I got in touch with Kat and Lalit, the founders of Vareto. They were trying to build a modern FP&A (financial planning and analysis) platform. Many designers might say, "That's not a very exciting problem." But, coming from the finance world, this felt like a great fit for me. It's probably not a problem I would solve on my own, but it's an interesting problem that I was uniquely able to work on.

How did Vareto compare to your other startup experiences? So, I joined Vareto as a designer right after they raised a seed round on an idea with no product built yet. There were about five of us, and it was really fun to design the brand, set up the design system, and design all of our initial products from scratch. I joined almost every customer and sales call. It felt much earlier stage than Bread and with some experience under my belt, I felt like I could make decisions with more confidence. Because there were no PMs, I ended up basically being the PM. I talked to customers, designed the solution, and then ran the planning meetings with engineers.

I had stepped in and out of the PM role at Bread, but this time I wanted to give it my focus. Kat and Lalit were very supportive and let me hire a designer so I could transition into leading product.

What was it like? As designers, we often get frustrated with PMs, they control the roadmap and make all the important decisions, and they’re always telling us what to do. After being a PM myself, I definitely developed more empathy. It's really hard to be a PM. It's so much work, and with the power comes a lot of responsibility. You have to be on top of all the engineers' work to make sure they are unblocked and shipping bug-free features. You have to know what customers and prospects are saying, turn that into a roadmap, and make sure your designers and engineers have the right amount of context to know how to move forward.

It was especially challenging at a startup working on a niche problem where everything is undefined, and none of the engineers or designers has really “lived” the role of the customer. It also sparked this thinking that if I'm doing this really hard job where I have to be responsible for a little bit of everything...maybe it's time for me to do that for my own company. It also made me realize that if I ever went back to working for someone, I would probably want to be a designer. That was the sweet spot for me after going through all of these different iterations.

So, from Vareto, how did you and David get started? David and I have wanted to start a company together since we were at Bread. When I was at Vareto, and he was at Google, we started talking about ideas we wanted to pursue. The one we were most excited about was building a more interactive way for people to learn how to code and for instructors to build courses.

I was open with my boss, Kat, that I wanted to work on my own startup. I probably wouldn’t have done this at any other company, so huge credit to her for building a culture where I felt I could be completely honest. I told her that I wanted to start a company and go full-time on it in a few months. She was incredibly supportive throughout the transition period and even ended up investing in us.

And so, we had this multi-month period where David and I were both working at our jobs and slowly working on a prototype on the side.

The real forcing function was when we realized that Y Combinator had a deadline for their next batch in a week and we decided to apply. A week! I remember it being very short! Yeah, this was where I was like, "Okay, this week I'm winding down from my job, and there's no urgency on the startup yet. I'm going to visit a bunch of museums." But then that all changed. When we got in, it became real. We needed to move quickly on this. And we need to make a lot of progress because there were all of these deadlines. The application, the interview, and then YC started in January with a demo day and fundraising in March.

What were some learnings or interesting moments that brought you to where you are today? I can't believe it's been basically a year! It feels like it's been three or four years.

The biggest learning is that it's really hard to build a company from nothing, especially getting people to pay to use what you're building. We went into YC to build this marketplace for programming courses and built a pretty powerful product. We're pretty good at designing and building, but the hard part for us is selling and getting people to use [the product]. We're not naturally self-promoting or super extroverted people.

One of the most valuable things about YC is that you’re building alongside a bunch of talented and ambitious people and you see what success looks like and how fast everyone else is growing. It's a good kind of peer pressure where you're like, okay, we're clearly not moving as fast as the best people, what can we do differently?

This helped us realize that programming education wasn’t the right problem for us to solve—it’s a very competitive industry and we weren’t the best team for it. So, we made our first pivot. We took our technology and shifted the focus to helping companies building technical products like APIs create better demos for sales and marketing. We got our first customer within a week, raised a small amount of money. From there we hired our first engineer, Gerardo, and went head down into building our product.

Again, we built a product that we were proud of, but sales went much slower than we wanted. More importantly, we realized that this was a problem we stumbled on and not one that we were passionate about or had any expertise in. We were too reactive with our first pivot, so this time, we thought more deeply about what to do next.

We started from scratch and started thinking about what interesting problems we were uniquely equipped to solve. We threw out a bunch of ideas, with a rough thesis that AI was going to enable products that weren’t possible in the past. When you entered YC, AI was gaining traction in the industry. Yeah, in our batch of YC, a meaningful percent of companies focused on AI, but the next batch was almost completely AI. GPT-4 came out at the end of our batch.

One idea that quickly bubbled to the top of my list was that user research is very time-consuming. I had actually written down this problem in multiple notebooks over the years.

You and I have done a ton of research at big and small companies and it’s always a challenge. Yes! First, companies don't do enough research and often skip the step because it takes up too much time. If you actually want to test prototypes with a customer or do some foundational research before writing a PRD, it takes weeks because you need to find people, schedule interviews, have a bunch of 30-minute conversations over multiple weeks, and then read through all these transcripts to pull out all the insights.

When I faced this problem in the past, I didn’t have an idea for how to solve it. But, with what language models like GPT-4 are good at, it became obvious to me that this was the right time. AI could turn surveys into rich user conversations, and do the analysis for you in minutes.

It became my obsession and I wouldn't shut up about it! laughing, David and I would be talking about our old product, and I'd be like, "Oh, what about this? Here's an article I found on user research."

It was obvious to you and you started sharing on Linkedin and with your network connections. People started contacting you because they wanted to have these conversations—especially folks in the design and research worlds because we know this is a big problem. Could you talk a little bit about how you approached connecting with your community and how that brought you to the current version of Versive?

Posting on Linkedin and reaching out to people in the industry was really useful. When we started, we talked to dozens of people: researchers, designers, marketers, PMs. People from three-person to 10,000-person companies across all industries. Every company is trying to understand their customers in some way.

We started off working with startups because they were the most open to trying a new product. We built an MVP that allowed users to create a conversational survey where the AI would ask dynamic probing questions. We convinced a bunch of startups to use our product to launch real studies. We learned that the frequency of research for smaller startups was too low for them to pay to use the tool so we moved onto trying to build a more robust platform for larger customers. If you're in a thousand-person company, you have multiple pods constantly trying to understand customers. Employees have less context and understanding customers becomes harder but also more important

We signed our first paying design partners and worked with them to build out tons of new features. We shipped AI analysis tools, a better study builder, more question types, voice interviews, usability testing, question logic, and dozens of other big features. And that’s about where we are now. We’ve brought on some name-brand customers and we’re working with them to continue to evolve the product.

Now that you're at this stage of your career and life, do you feel like you were able to draw from previous experience or pull something from your toolkit to help you grow? And on the flip side, what are new things you're trying to learn or something that you're experiencing for the first time?

On the first question: yes, a little bit of everything. Ultimately, I'm solving this problem because it was a problem that I faced in my previous roles. That helps a lot when you're working on a startup. I can make better and faster decisions because I have more context and intuition.

I think being a designer and, in particular, working at startups has helped too. To start a software company you need to be able to do things: build the product and get people to use it. Being a designer helps you design a better product, but that alone is not enough. You also need to understand the business, figure out how to sell and market what you’re building, solve the thousands of operational problems that come up, and ideally also be able to pitch in on writing code. Working at startups has made me comfortable with ambiguity and learning on the fly.

On the second question, almost everything is new. David and I have to make every single decision, there’s nobody to delegate to. If I want to move things forward, I have to figure out how to do it myself. I’ve become a much better programmer because writing code is the ultimate way to improve the product. I went from barely understanding Javascript to shipping tens of thousands of lines of code in the last year. Some weeks, I spent 50-60 hours writing code. Thank god for ChatGPT.

Also, I was exposed to different roles like Sales and Marketing at startups but unless you've done the job full time, it's not the same. I've sat in on sales calls, but when you actually have to take the sales call yourself and be willing to be uncomfortable and ask questions, present prices, and ask for commitments, that's hard, and that's new for me. The other thing that's really new for me is putting myself out there because if it were up to me, I would just stay in my room and write code. I wouldn't be posting on Linkedin for fun to build a following, but it’s really important for the business.

Overall, this is definitely the hardest job I've done, where I've had the most self-doubt because I'm still not good at it. And the ceiling for being good is very high. That’s scary but also very exciting.

What are you most excited for next? The story for Versive is still being written. I'm very optimistic about how things are going. Things are moving faster than before, and it feels right. We're excited about two main things. The first is that we still need to build a lot for the product. We have a big vision and want to build the next big customer research platform, like Qualtrics or UserTesting and there’s a lot of exciting work to do to get there.

Secondly, we started working with small teams. They were happy with us, but not all were willing to pay. We've shifted towards starting to work with larger companies, and we’re now working with companies we admire that have thousands of employees. And we're really excited to see where that goes. Going forward, It'll be my focus to figure out how we bring on more of these large customers and make them successful. It’s exciting and daunting at the same time.

Why does any of this matter to you—from all your decisions in your personal life and career? Well, we have to work, or at least I do. You spend a lot of time and mental energy working, and in an ideal world, the work is interesting. And you're working on something that you want to solve or teaches you new things. That it's fun and engaging. And that's something I learned about myself: that when I leave a job, it's because I get bored and don’t find fulfillment.

So now, with starting a company, I see this as an experiment I’ve wanted to try for a long time. I have something that I want to put out there that solves a problem—one that I've experienced. While it's not saving lives or anything, [being a founder] is the most interesting and fulfilling thing I've done. I'm creating something from scratch and solving a real problem for people. I'm learning way more than I ever have learned, and at the end of the day, I'm doing this for myself. I'm not answering to anyone other than customers.

…[being a founder] is the most interesting and fulfilling thing I've done. I'm creating something from scratch and solving a real problem for people.

And at the same time, when you're working at or on your own startup, you definitely have less time for your personal life. But I think you can still make time for it by cutting out other things in your life that are not valuable. I still make time for things like spending time with my wife, friends, and cat. With Mochi! Yes, and I want to pursue my hobbies like climbing and running and I’ve found that I can still make time, even in my most productive weeks at work.

Are there any misconceptions about you, the work you do, or the industry you're in? A couple of things. When you have a job, people tend to put you in a bucket. People assumed that finance people are analytical and obsessed with making money. That they only care about these things. And then, when you're a designer, people assume you just care about the creative side of things. You only think about the user and don't understand the business. But, there's a lot of fluidity in people's careers. We both know a lot of people who've done all kinds of different things. If you're in a career and you're feeling like this isn't for you, you can switch.

…there's a lot of fluidity in people's careers. We both know a lot of people who've done all kinds of different things. If you're in a career and you're feeling like this isn't for you, you can switch.

Another misconception is that in startups, I feel like you hear a lot of extreme opinions. Like, "Oh, I can never start a company because it's so much work” or “it must be nice starting your own company where you don't have to answer to anyone." The truth is more nuanced. I definitely work more than I used to, but I still have time for my personal life. I don't always feel overwhelmed or burnt out. And yes, I have a lot of freedom, but I also feel a lot more personal responsibility. In some ways, it's just another job with its own pros and cons that many people should consider.

There's fluidity in careers but also in the focus on different problems. Even the misconception of time, which is how much time you're spending versus how much your focus is on work versus personal, is all gray. It sounds like you're advocating for the fact that there's a lot in the in-between. Ultimately, it's really how you put those pieces together and decide where or what you want to pursue. I agree with that; maybe the overarching thing is that there's no one way to do things. Often, people ask, "What's the right way to do this?" or "How do I optimize my career?" But having done all these different types of work at different companies and roles, I don't think there's a right way to do things. It's perfectly valid to be working in a big tech job that is paying really well, and you spend your time on other parts of your life. It’s also perfectly valid to pursue something you’re passionate about with all of your waking hours. It just depends on where you are, your priorities, and something that you should reevaluate all the time.

I love that answer because we realize there is no right answer as we age. When we’re younger, we look to more experienced people to tell us what to do. But the moment we realize that no one can tell us what to do and that we must make that decision ourselves because the decision is in our hands at the end of the day. And it's all about trying. Whatever you try, let's just do it—and that's been a recent learning for me.

When you're younger, you think of time differently. Everything is like a rush, and you're a bit more judgemental when you say, "Oh, I don't want to be where this person is at age 35, right?" And you're like, "I want to be here instead!" or "Why is this person doing this with their time?" And it's now like you appreciate where you are, the decisions everyone has made, the journeys people have taken, and you understand why people took these paths. I don't think there is a right answer.

…you appreciate where you are, the decisions everyone has made, the journeys people have taken, and you understand why people took these paths. I don't think there is a right answer.

I wouldn't have expected to be doing this when I graduated from college. Yup, you would have been in private equity! And I would have a lot more wrinkles and gray hair. laughing

If you could pick an Eric at any point in time in the past, what advice would you give him? I'd probably go back to high school or college. I would encourage myself to pursue things I was interested in more seriously, regardless of whether they were "the right things" everyone else was trying to do.

When I was younger, it took me a while to figure out that I was interested in art, so maybe I should have pursued that more by taking classes in school, building out a portfolio, and going to a design program. Or maybe, in college, I should have looked into spending all my time on entrepreneurial and design-related things.

Give us a list of 3 things you'd recommend. You choose the topic.

Libby the Library app or libraries in general. A lot of US cities use this app called Libby, which lets you rent books. I use audiobooks the most, and I started using this app around Thanksgiving. I hadn't read any books in the past two years, but I've read eight or nine books in the last couple of months.

Get a smart oven! A smart countertop convection oven changes the way we cook. Big ovens take 30 minutes to heat up, but these take two to three minutes. It cooks things faster and doesn't make your entire apartment hot. You could literally bake a chicken for lunch if you wanted to.

Use AI tools to make your job and life easier. Use ChatGPT and Claude. Use it to negotiate your rent like Leslie did! Or use it to write code or learn something new. It's been one of those things that has saved me so much time. It gives you specific answers and doesn't require you to read Stack Overflow threads for 20 minutes just to answer a question.

What is your favorite or current song you have on repeat?

Please Please Please by Sabrina Carpenter

Enjoyed the Conversation with Eric Li? Learn more about Eric's company, Versive, a faster, more effective way to conduct AI-powered user research at versive.com. You can also find him on Linkedin.

Eric is also passionate about giving back to Animal Care Centers of NYC

Animal Care Centers of NYC (ACC) is a New York-based non-profit working to ensure that stray and surrendered pets have access to food, shelter, and medical care as they wait to find a loving home. A donation was made to Animal Care Centers of NYC as part of this Conversation.

You can support Animal Care Centers of NYC by donating directly and consider adopting or fostering a furry friend.