Possibilities with Laura Sandoval

Meet Laura Sandoval, a Chilean and Peruvian designer and creative based in Brooklyn, NY.

Meet Laura Sandoval, a Chilean and Peruvian designer and creative based in Brooklyn, NY. Laura moves through life with a deep curiosity—grounded in culture, community, and a constant openness to possibility. She reflects on growing up in the Chilean countryside, adapting to city life in Santiago, and how YouTube and filmmaking first sparked her creative drive. A short stint at film school in Peru eventually led her back to Santiago to pursue design, where she learned from niche-obsessed mentors and balanced her studies with professional work—often out of financial necessity. By graduation, Laura had already launched apps, joined startups, and found herself at Cornershop, a leading grocery delivery service, just weeks before its acquisition by Uber. That moment kicked off a whirlwind: leading design, scaling a team, integrating two companies, and ultimately relocating to New York—always following what felt possible.

Interviewed in April 2025 | This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Please introduce yourself. I'm Laura. Everyone calls me "Lau," which is short for Laura. I'm a product designer and human being. I just moved to Brooklyn from Santiago, Chile, which I'm so excited about. I would describe myself as curiosity-driven because that's what ultimately drives me.

Let's go back in time—perhaps your childhood in the countryside. Was there anything you'd like to share that stuck out to you? I really remember growing up in the countryside as a "free era." We used to live with my parents on this giant piece of land, we weren’t farmers but we did have chickens, dogs, and cats. I remember everything feeling…possible. I’d go out in the morning, explore through the fruit trees, play with rocks and sand… I remember exploring the hills around the area and having this vivid sense of freedom, which was very inspiring.

Did you grow up with many siblings or just your parents? It was mostly me and my mom. I was born in Peru—my dad is Peruvian, and my mom is Chilean. They divorced when I was around one year old, then my mom and I moved to Chile, and she married another man while my dad was still in Peru. Somewhere along the way one of my brothers, Andrés, moved with us from Peru for college.

My step dad and brother, who we lived with in the countryside, were always in Santiago —the capital city— for work and college, so it was mostly my mom and me in the countryside during the day, and they’d return at night. I did have a lot of friends from school, but because we were in a remote area, it was hard to meet people sometimes, or it'd have to be in a very arranged setting. So I spent a lot of time by myself.

What did you gravitate towards doing when you had so much alone time? I had a lot of imaginary friends, though I don't remember any of them, but my mom always reminds me. I would always be out and around exploring and "inventing" new things. Anytime I had a crazy idea, I would ask my mom, "Do you think this is possible?" and she'd say, "Yes!"

We moved to Santiago from the countryside when I was nine. My grandparents and extended family were also in Santiago, so it made sense for us to move. Moving was a big cultural shock. Moving from an environment where it was just us and nature to this huge city with a subway system and all these people and the roughness of the day-to-day, whereas the countryside was a bit more free flow and peaceful.

What was that transition from a smaller community to being immersed in the city as a nine-year-old like? What was your first impression? It was both exciting and frightening at the same time. I really struggled to fit in at the beginning, and there was a lot of bullying as well. Me being “the weird kid from the countryside” was a thing I remember. But at the same time, there were so many possibilities waiting to be explored within the city that it was also very exciting.

How did you begin to tap into those possibilities? This era was marked by the start of having internet access. At age 10, we started having internet access at home. It wasn't the internet we have today, where it's easily accessible at any given time. Wait, was it like where you'd get a CD in the mail and you put it into your big ol' computer? It was the kind of internet where you had to choose between the internet or using the phone where if you picked up the phone while someone was using it, you got the "eeeerrreeeeezzzzz" sound! Yes!!! Laughing

Since I was struggling to make friends in school, I ended up trying to find a place on the internet where I started to make a bunch of online friends—which, in hindsight, feels dangerous but turned out fine. I also leveraged a lot of the "freedom" I had when my mom would let me go, for instance, to the park by the corner near the house, but in reality I’d be taking the subway. I was a very irresponsible child, going to meet up with my online friends across the city. More than a decade later, I still keep in touch with these friends.

At the same time, I was also finding my place on the internet. I’m going to age myself here, but I loved the show iCarly. I loved the idea of having a web show, so when I discovered YouTube, I went crazy. My first neighbor in Santiago showed me that anyone could upload anything to YouTube—at first I thought only an agency could do it. It's like the one episode in The Office where Michael Scott says, "I've got to make sure that Youtube comes down to tape this."

I started uploading videos to YouTube, like stop-motion Legos and me talking to the camera. I was also trying to find a community on the internet. Were you learning how to do this on your own through the internet? Yes, and googling a lot. A lot of folks had similar experiences when the internet was coming up, and we were all really young trying to figure out things online if we didn’t know how to do something.

Did you notice if there was something you were learning that you also really enjoyed doing? The stop-motion stuff was really fun, especially spending two or three hours doing it and then seeing the final results. Not only it brought my toys to life, it also taught me how to adapt things like timing or how drastic to make the moves for it to look good. Having that quick iteration cycle going was really fun.

I was also playing with Microsoft Paint and trying to learn how to do frame-by-frame animation, which was a bit slower compared to recording with an actual camcorder but also really fun.

Wow—this reminds me of the video you created and shared about the Chilean money system. From how you confidently spoke to the camera to the editing and script, you were spot on. It came from your experience doing YouTube! A hundred percent. It was so fun for me to make because it was like a reunion for that side of my life. Like a good excuse to go into Final Cut Pro, color grade, and even experimenting with new filming techniques. I always love it when I get to overlap all the different past versions of myself.

During this time in your life, as you were transitioning into city life in Santiago and making friends online and offline, what and how did your friendships evolve? During this YouTube era, I started forming all kinds of friendships. Most of these friends were a lot older than me. I was 12, while many of them were 17 or 18, some already in college. Looking back, I have no idea why they hung out with me, but I love them and I love that they did. Back then, we’d smoke cigarettes together and go on trips for meetups with local YouTubers, trying to build community. I tried to attend every meetup, which started in local parks where I’d go by myself, but once I started having a more established group of friends, we'd travel around Chile to go to larger meetups together. Those were my first times traveling without my parents, which was scary but also exciting.

I remember going to Concepción —a city in southern Chile— a lot. I still have many friends there, and now that I’ve moved to New York, one of my besties—from Concepción—came up to help me with the move. I keep going back to this city and have such an emotional connection with it.

Concepción was also the first city I traveled to on my own. My friends and I eventually started making more friends over there and I even started dating someone, so I was always visiting. It was so much fun. With this more established group of YouTube friends, we launched our own projects, including a parody account of one of the biggest Chilean YouTube channels at the time, based in Concepción. You're just drawn to this city over and over again!

I was only 14 when we posted a parody of one of the biggest Chilean films at the time, and the film director actually reached out. All of a sudden, TV producers were asking if we wanted to work for them, and all these doors swung open toward a possible media career—it was incredibly exciting.

Were you seriously considering this career path in film? What was it like hearing about this at such a young age? It was weird, to be honest. We weren't expecting it. I was just having fun with my friends, but seeing that we could put something out there and people would find value in it, whether intended or not, was eye-opening. We’d even get stopped on the streets sometimes, especially when we went to Concepción. It was quite a niche experience.

I continued to be an independent Youtuber into my adulthood. Somewhere along the way, my friends and I ended our side project, but we continued being friends, collaborating, and traveling together.

But then, I decided to move to Peru and somewhat doubled down on YouTube. In Peru, I had a very similar experience—growing my channel independently, producing more and better quality content and seeing more people find value in it in return. It again got the point of some people recognizing me in certain places, but thankfully it always remained niché as well. It did scale to a point where it started being a bit uncomfortable for me, though. Well, yes, you're a normal human being. Exactly.

I remember this one time when I was 17 in Peru. I was unhappy with a few things in my life and thinking about moving back to Chile. I was walking down the streets of Lima, about to cry, when a girl recognized me from the internet and asked if we could take a picture. Oh no!

I did also receive so much love, which was really special. People would sometimes offer to buy me coffee or dinner if they saw me out and about by myself, and I got so many letters from younger kids in my high school who watched my videos when I graduated. I still keep and cherish all of them, and brought them with me to New York.

I moved from Chile to Peru in 2014 because I wasn't very happy there. I really liked Santiago, but I didn't like my high school. I felt it was very uninspiring. Any time you tried to do anything outside the books, the entire school vibe was to repress it in some way.

I also just hated school. I always did terribly in Santiago. In Chile, high school lasts four years, but in Peru it lasts three, so I thought it was perfect. That meant I could move and, as a bonus, do one less school year, so I left for Peru and moved in with my dad.

Moving to Peru really helped me explore my creativity more. In Chile, the school was more about getting your academics done and maybe some traditional extracurriculars like sports, whereas in Peru it was more freeform. For instance, I had some very basic knowledge on how to make and publish websites (using Apple’s old iWeb app and some YouTube tutorials), and while in Chile that was considered a distraction, or even something to make fun of, my Peruvian high school was really great at celebrating those qualities, and creating the space for students to explore them. Is this a cultural thing? I think Chile has a very strong culture of preserving the status quo. Change can be very challenging and everyone is sort of expected to do similar things, I feel like. Another example is that being a YouTuber or having side projects was very encouraged in Peru but a reason for laughter in Chile, so it was a refreshing change.

So, as you double down on being a YouTuber in Peru, what happens in this era that makes you consider moving back to Chile? It's all connected to filmmaking and design, actually.

Of course, I had an amazing time in Peru and made many good friends with whom I still keep in touch. I also made some really special connections with my teachers, who became mentors, which is very nice since I didn't really have the chance to find them in Chile.

Also, because I had these very chaotic preteen years of smoking, partying, and being out and about, I was no longer as interested in that side of things in Peru, so I really got the chance to become more professional with my side gigs. I became better at coding websites or making YouTube videos, and I started to think of those things as a potential career, especially as I was approaching adulthood at that time.

After high school, I had a booming YouTube channel at its prime. I also started working as a freelance photographer and videographer when I was 17, through a made-up “studio” I created. I coded a website for it and built a portfolio with some of my work, and called it a studio so it’d look more professional, but it was actually a one-woman operation. My older brother, who always had a business mind, really saw the value in what I was doing, so he helped me a lot.

My brother Andrés shaped a lot of who I am today. He gave me endless frameworks to think through life’s challenges, took me to New York for the first time, and back in Lima he helped me connect to people interested in my work, as well as how to charge for it. I always wanted to do everything for free because I didn't know what value I could add, but he kept me grounded and even helped me invoice when dealing with larger clients. It's great that you had someone look out for you and teach you to charge for your work at a young age. Totally, and his guidance continues to be useful today, many many years later. I’m extremely grateful to have him in my life.

So, after high school, I decided to study filmmaking in Peru. My plan when moving to Peru was always to return to Chile, but I had made such special connections there that part of me wanted to stay, so I decided to give it a shot but then quickly realized that while intentions were good and people were eager to set you up for success, the infrastructure just wasn't there yet. Film school was very cool but also very limiting. The school had only been around for like 2 years, and the Peruvian filmmaking industry wasn't as big or disruptive, so it started feeling a bit uninspiring.

When did you start to notice this? About two months into film school, I remember having too much free time and generally feeling like I wasn’t being intellectually challenged. They would teach us how to use basic software and make us do written exams on how to use stuff like Adobe Premiere—I kept thinking, why can't we figure this out on our own? It felt like we were investing a lot of time, energy and resources to learn how to use a hammer instead of how to build a house.

I also realized that, even though I loved filmmaking, I was a terrible cinephile. I haven't watched many classic movies, to be honest, and I’m not as drawn to them as I feel like I was expected to be. That's how I feel about design sometimes.

What happens next after you realize that filmmaking and film school in Peru weren't the path to go down? I got into a fussy moment career-wise. Filmmaking had been such a core part of my life at that point that without it I wasn't really sure what I wanted to do next. And so, my brother, once again saving the day, said “let's think about where you’d want to go, and then we can reverse engineer which career path could take you there.” Jamming with him about this made me realize I ultimately love creating, and putting things out there into the world that hopefully add value to people’s lives—filmmaking was one of them, but it wasn’t the only one. We arrived at design cause it felt like the most flexible path forward. I could still design a film or a media piece, but I wouldn’t be limited to one format. I started looking into design options in Peru, but they were basically non-existent, so I ended up going back to Chile, which has one of the best design schools in LatAm.

I didn't really learn about design until I got to college. I wasn't exposed to the career nor knew it was a viable option until maybe then. When did you know doing design was a career? I was always very interested in technology growing up. In parallel to this YouTube era, I’d always be mocking up graphics, websites, and eventually even basic apps on software like Keynote or iWeb. It proved really useful to support the sidelines of my YouTube channel, too. On top of this, my brother would always talk to me about new trends going on at the time, like “design thinking,” so by the time I joined college I guess it wasn’t completely foreign to me, but it was definitely recent knowledge as well.

So, how did the move back to Chile happen? Similarly to how I moved to Peru, I asked my mom if she would receive me back, and she generously said yes. So I quit film school and spent a few months doing nothing but my YouTube channel, while waiting for the second admissions window to open. At this time, I also began to have a slight obsession with transit.

Slight derail —pun intended— but navigating Lima as an adult feels very different from navigating Lima as a teenager. Lima is a very large and chaotic city, so moving around is tough. Lima’s first Metro line opened in 2014, almost 30 years after construction began, which is insane. People mostly move around through shadow buses called “combis”, which are insanely cheap but have a lot of unwritten rules around them and aren’t the most reliable. This lack of infrastructure made me realize and appreciate how lucky I was in Santiago to have things like predictable routes, a stable and growing subway system. In contrast to Lima, Santiago opened its first Metro line in the 70’s, and is on track to open its 9th line by 2030. Thinking back to my 10 or 12-year-old self, navigating the subway and being able to move safely around the city was really special in hindsight.

I began obsessing about transit as a service and how different cities approach it, optimize it, and ultimately design it. I asked myself, if Santiago was to design a graphic identity for its transit system, how would I approach it? What do other cities take into account for theirs? I read about Transport for London, the MTA, the beautifully designed Moscow Metro Map, and ultimately allowed myself to wonder and explore these questions through design, always sharing my thoughts and explorations on the internet.

This created a great vicious cycle for me cause it ultimately allowed me to jumpstart my design career through something I was personally passionate about, and by the time I started design school, I already had a small design portfolio and had met with all these people in the industry who were somehow interested in what I had to say, from academics to Chile’s own Vice Minister of Transport, who eventually became a Twitter mutual.

That's awesome. When I speak with early career designers, many are conflicted about showing "real projects" on their portfolios. What you had was a real project—you conceptualized something, shared how you made it real, and had conversations that grew from it.

Totally. The main difference between a real and conceptual project is usually that one was "requested" versus the other wasn't, but that doesn't really matter at the end of the day. Design can be a really powerful tool to express a point of view, and to visualize how we envision reality to be. Whenever I talk with early career designers, I try to emphasize that we don’t need anyone’s permission to do that.

“Design can be a really powerful tool to express a point of view, and to visualize how we envision reality to be. Whenever I talk with early career designers, I try to emphasize that we don’t need anyone’s permission to do that.”

How and when did design school come in? Taking a step back, so in Chile you need to take some standardized tests to get into college, but because I finished high school in Peru, I had a slightly different process. I didn't realize it then, but applying to design school through this special process was a very competitive and risky move, cause there are only five slots per admission cycle, and you’re competing against up to 60 other folks looking to get in through one of them, including Chileans who studied abroad, people with special needs, distinguished sport alumni, etc.

The most crucial part of the process was an interview with the curriculum director and a panel of teachers who evaluated each candidate at the end. It was sort of like a job interview—they asked questions about design, how I’d approach different problem spaces, and most importantly, what would I do if I don’t get in. The fact that I had all this work prior to the interview—the photography & filmmaking studio, the transit design projects, etc—made a world of difference, because I was able to let my work speak for myself.

Everything was publicly accessible through my websites, so they were able to see it during the interview and ask questions about it. I told them if I didn’t get in, I’d double-down on these projects and reapply on the next admissions cycle, but luckily that wasn’t necessary. Wow, and the question "What would you do if you didn't get this opportunity?" is such a good one because it can be tough to answer. Totally. It caught me off guard at the moment, but I’m happy I could leverage it to showcase my work. The school’s academic coordinator later told my mom and I as I was enrolling in school, that the panel had been “blown away” by it and were honored to have me. It was truly special.

What was your design school experience like? My design school was an aggregator of very talented folks, each with their own niché interests. My curriculum director, who later became a dear colleague and mentor, was also obsessed with transit and had his own wayfinding design studio on the side. We’d talk for hours about maps, mobility, graphic design, typography. I had teachers obsessed with color, science and history. I had teachers who had dedicated their careers to lighting design, and some who obsessed about fashion or the political implications of what we were putting into the world. Everyone had their own interests and unique path to design, and the combination was truly greater than the sum of its parts.

We all started on the same curriculum, where we studied the history and foundations of industrial and graphic design. It was the opposite of my experience at Peruvian film school in that the emphasis was always on teaching us how to think and quickly exposing us to trial-and-error cycles, rather than leading with specific tools. We almost didn’t touch a computer for the first few years. We’d do lots of sketching, paper-cutting, and research, and present weekly progress on our assignments through posters or decks we also had to design. We’d spend days at the workshop working with wood and take turns sleeping on-campus while working with fiberglass throughout the night. I learned very quickly that I was terrible at industrial design.

I guess my journey—I don't want to say it got interrupted—but my first year was marked by my parents not being able to afford design school anymore. My student loan didn’t cover the entirety of the cost either, so it was either quitting design school or figuring out a way to pay for it by myself, which is what I ultimately did.

I began socializing that I was open to work and, thankfully, managed to get the ball rolling quickly. I got poached by a local graphic designer—who was familiar with my work through Twitter— to work as his assistant for a few months. My curriculum director, who had always said he’d love to work with me at some point, then offered me an assistant role on a last-minute project to redesign Santiago’s transit graphic identity. Eventually, I landed at a local cycling-tracker app start-up as a Design Engineer, thanks to the founder also knowing my work through social media.

As I navigated the professional world and learned from all of these designers who were far ahead in their careers, college started to become a background activity. I had very little free time, juggling both work and college, so I began optimizing my college involvement to prioritize the two or three classes I felt most beneficial for my professional growth, and did just enough for all the rest.

Did you finish college? I did. Chile has an extra year compared to the United States, so we have a five-year program. I finished at the four-year mark, the bare minimum for the US and the rest of the world. Some industries in Chile, like the public sector, would limit my seniority for not having that fifth year, but it’s not really the case elsewhere and even internally it can be replaced by a masters degree if I wanted to.

I ask about finishing school because not everyone does. Yet, finishing school doesn't equate to success. It's more about personal decisions and timing to get you where you want to go versus checking every box. In this case, since you were already working, you decided not to check the fifth-year box. Absolutely. Some of the best designers and product thinkers I’ve worked with didn’t have a college degree, including my old company’s Head of Design and Founder/Head of Product. It’s a really personal choice. I did want to quit at many different times, but was encouraged by many mentors —including my brother Andrés— not to, since having a professional degree would be really helpful if I ever wanted to expand outside of Chile. Once again, he was right!

How did you go from finishing your degree to becoming the Head of Consumer Design at Cornershop? I started leading Product Design for Consumer apps at Cornershop —the largest grocery delivery app in LatAm— in 2020, but 2019 was the year that glued all the pieces together for me, and really solidified the foundations for everything that came after.

While I was working as a Design Engineer at Kappo, the cycling-tracker app, I was lucky enough to pick-up a few high-paying freelance jobs. My curriculum director and I had become close working buddies at this point, so he’d always call me to collaborate on new gigs. I was able to pay off the remaining year of my college tuition in advance and shifted gears to my next personal goal—moving into my own place and becoming financially independent.

At this point, I had also launched a few independent transit apps, like a Facebook Messenger chatbot for Santiago’s transit system, which the Ministry of Transport tried to acquire the year prior, and an iOS app for checking your transit card balances, which I still maintain to this day.

Since I no longer had to earn a steady monthly income to cover my college tuition, at least until the next year, I quit my job at the cycling-tracker app and started thinking about my next chapter.

One random night, I stumbled upon a tweet from Cornershop’s Creative Director, Daniel López Rivas, who was both a Twitter mutual and the owner of one of my favorite coffee shops in Santiago, saying Cornershop was hiring across most of its departments. We were both familiar with each other’s work, so we got to talking and he introduced me to Matías Martínez, the company’s founding designer and Head of Design. He was also familiar with my work.

As a side note, it had always been my dream to work at Cornershop. I had been a loyal user since I moved back to Chile in 2016 and always admired their craft and commitment to quality. They were truly unmatched. I actually applied to work there as a customer service agent back in 2016, before starting college, but was rejected. Well, thank goodness, because it led you here!

Exactly!

So I started chatting with Matías on a Tuesday, right after talking to Daniel. We met for coffee on Thursday —at Daniel’s coffee shop— with Matías and Osvaldo Mena, Cornershop’s Head of Engineering at the time. They both had my apps installed on their phones. We talked for a few hours, discussed my salary via Twitter DMs the night after, and I joined Cornershop the following Monday as a Design Engineer. It’s the fastest I’ve ever been hired, I think.

Incredible. Around 2021, I recall Uber acquiring Cornershop, which led to us eventually meeting in 2022 and working together. Could you share your experience leading up to the present day, especially from being part of a team going through an acquisition? Joining Cornershop was a pivotal moment in my career. I remember going into the office before and after classes feeling a strong sense of “wow, what the hell am I doing here?” We were around 300 people, maybe six on the design team, and everyone was so talented that I felt like I was learning more each time I went into work than I’d learn in a month of design school. It was truly inspiring.

And to make things even more exciting, right after I joined, news broke that Uber was acquiring a majority stake in Cornershop. I remember my brother texting me that day: “Did you just accidentally land a job at UBER?” I couldn’t believe it.

A big part of why Cornershop hired me in 2019 was my independent apps—I wanted them to feel smooth, snappy, native to mobile phones, but I only really knew how to code for the web, so they were actually coded like a website, but packaged like an app. I spent hours obsessing over the details, and would always be studying ways to make them feel snappier or to make interactions smoother. I remember Matías —who’s also the best iOS engineer I know— telling me he thought my apps were native felt like my biggest achievement.

Coincidentally, Uber wanted to leverage Cornershop’s tech stack and expertise to tap into the grocery delivery market, and Cornershop wanted to leverage Uber’s scale across Rides and Eats to reach new customers, but delivering groceries is a whole different game than delivering on-demand meals, so we couldn’t “just add grocery stores” to Uber Eats at the time. Building support natively would’ve been a gigantic undertaking, especially pre-pandemic where demand didn’t quite justify it yet. So both companies decided the first step towards integrating would be to somehow integrate Cornershop’s website on both Rides and Eats. The big issue was… it felt too much like a website. It didn’t even work on mobile.

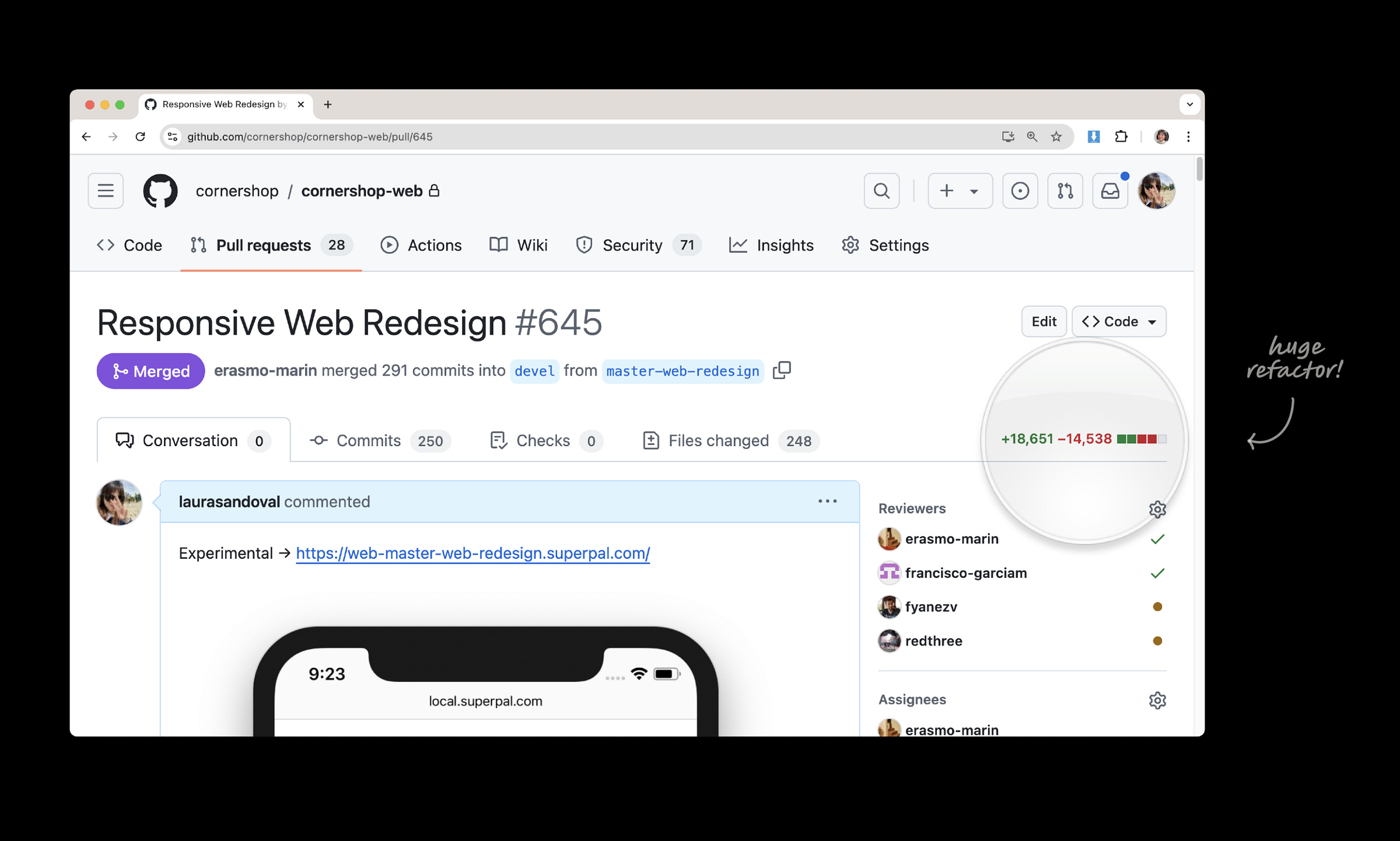

Matías and Osvaldo quickly tapped me for the challenge, and I was asked to make Cornershop’s website “responsive”, which would eventually allow us to theme it as an Uber product and plug it into Uber’s ecosystem. I guess I had the right obsession at the right time!

Taking on this challenge was no easy task though. It was my first time working on such a large codebase, so I leaned heavily on more senior engineers to navigate it. We ended up rewriting almost 20 thousand lines of code—at a time where “vibe coding” and generative AI weren’t a thing. Again, I obsessed over the details to keep the illusion of a native product. I wanted Uber Grocery to feel like a first-class citizen in Uber’s ecosystem.

All of a sudden, I found myself invited to all these sessions and dinners with the Cornershop founders, including the CEO, and Uber executives flying to Chile to check-in on what I was working on. The first time I gave a demo to the team, I remember everyone going: “Are you sure you’re on the website and not the app?”

We launched Uber Grocery only 5 months after, and added more than four billion dollars in annual recurring revenue through it in the following 3 years, before sunsetting the website.

As we scaled Cornershop towards the end of 2020, we decided to split our Product Design team into verticals. Our once-300-person startup was now on track to hire its 1,000th employee, and the timing felt right to scale our design operation into more focused pods. As soon as I graduated college, Matías asked me to lead Consumer Product Design. By that point, I had a proven track-record of shipping high-complexity projects, had worked with both Uber and Cornershop leadership, and, in the words of Matías, “couldn’t be fooled by less-committed engineers.” thanks to my early exposure to all sides of the business. He said he “couldn’t picture anyone else taking the role,” which was truly special—for me, it was a testament to all the previous pieces of my career coming together for the first time.

I was tasked with hiring our Consumer Product Design team, and leading the way for our iOS, Android, Web, and now Uber apps. It was one of the most challenging but fulfilling periods of my career.

And once again, you were open to the possibility. True! Thus, you were able to embrace the experience more. Your natural disposition seems to be to embrace what's possible, which is awesome!

Shutting down Cornershop and transitioning the team into Uber was a similar story. Uber had acquired the rest of Cornershop in 2021—making it the first Chilean unicorn and the largest acquisition of a Chilean company to date, and leadership decided we’d integrate everything natively the year after.

As a few folks prepared to leave, including our Head of Design, I randomly got a meeting invite on my calendar from Uber’s LatAm Grocery Director, who was acting as Cornershop’s interim “CEO.” The meeting was just him, me, and my HR rep. Honestly, at first I thought I was going to get fired. I had never spoken with him before, but he knew exactly who I was and wanted me to integrate Cornershop’s Product Design team—which had grown to 37 Product Designers and Design Managers across five verticals at that point— into the Uber org. He thought we’d only be able to migrate six or seven designers, so his ask was that I figure out the best way to navigate this and migrate as many people as I could. Woah! I had no clue that happened.

I had no instruction manual, but nor did I have one for anything that came before! So I just said “sure, whatever, we'll figure it out.”

Cornershop was pretty much still an independent company at this point, so I started by building as many bridges as I could. I set up a recurring meeting with Uber’s Delivery Design Director, met with Uber’s Delivery Design Program Manager to get a better sense of how things worked and how my team could better support the company’s design needs, and started poking around to meet with as many Product Managers and Designers as I could, to get insights, gain momentum and hopefully accelerate collaboration. My time with design leadership was limited, so I felt like the most efficient way to approach it was to gain as much context as I could myself instead of waiting for those times to get it. That way, when the time came to discuss logistics, I’d already be familiar with what was going on, and could identify collaboration opportunities independently.

On the other hand, at Cornershop, we didn’t really have much documentation or formal processes for a lot of stuff, so I worked with our own Design Leadership to proactively set up documents and Google Sheets for anything we anticipated could be useful during this time, like performance reviews, featured projects per designer, strengths, career paths, etc. It was, again, all about optimizing for efficiency and making sure we had everything we needed during those small decision making times with Uber’s Design leadership. I also started sending weekly updates to our broader design team —who had been navigating uncertainty for a while— to give a sense of momentum and continuity.

In the end, we managed to migrate at least 13 designers —more than twice than we’d initially estimated— to full time roles at Uber. It was bittersweet in that I had to let go most of my team, but this was also the first time in history a Chilean start-up integrated into an American company like Uber, so I’m extremely proud of the work we did.

Your role has shifted since joining Uber—what was that transition like for you?

Uber’s leveling process for Cornershop was a bit strange in that seniority levels were assigned by salary instead of role, capping the levels at “Senior” —typically reserved for department heads—and prorating by salary bands below. In my case, because I reported to our Head of Design, I was leveled one level below senior, and had to switch back to being an individual contributor to continue at the org.

We all got our levels as I was leading the migration, so this obviously blew up internally and suddenly I had to be the face of bad news. My main focus was on getting as many people as possible a role, and making sure all voices on the team were heard, so I remember spending many late nights on Slack DMs or impromptu Zoom chats with HR or the founders, who at this point didn’t have that much power themselves. I wasn’t paying much attention to my level in particular, and instead decided to trust that things would naturally find their place in the long run, and I’d find my place to add value again. Obviously, you've been able to do that to become a crucial member of the team.

Since joining, you've recently moved from Santiago to New York! What spurred the international move? I always dreamed about moving to New York, but never thought it’d be possible in my lifetime. I dreamt about it as a child and fantasized about living here when I visited for the first time in 2015, but could not see a path where that would happen unless maybe I studied for a Master's Degree or something like that. Uber has really changed possibilities for me in the last few years.

In 2023, I got to attend the Grace Hopper Conference, one of the largest conferences for women and non-binary people in tech, held in Orlando, Florida. I remember coming back to Santiago afterwards feeling not only inspired. But also like, regardless of my employer, I wanted to be where the action was.

At the same time, I had just bought and remodeled my own place in Santiago a few months prior and all the incentives keeping me at Uber—inherited from my previous role at Cornershop— were approaching their expiration date, so I found myself in between crossroads. Looking ahead 1 or 2 years into my career, for me it was either leaving Uber to start my own thing, or doubling down and pursuing an international move. It seemed personal and professional became intertwined.

Now that we're in the present day and you've moved to New York, why do any of your experiences or decisions matter to you? There's something inherently fun about making things that other people use. And so, looking back from the YouTube days to designing for Uber, I feel like the underlying fun part for me is the same. Working on something that’s bigger than myself, getting to meet and collaborate with fun and talented people in the process, and people finding value in what we decide to put into the world at the end—and then doing it all over again.

“There's something inherently fun about making things that other people use… Working on something that’s bigger than myself, getting to meet and collaborate with fun and talented people in the process, and people finding value in what we decide to put into the world at the end—and then doing it all over again.”

What advice would you give to a younger you? I probably should've been more unhinged. laughing Wait, explain! Well, thinking back to when we launched Uber Grocery, for example, I spent my 22nd birthday on Figma and VSCode rushing to get all the details ironed out for our upcoming launch the week after. It was a Sunday, and I had both college & work the next day. Sure, we were well paid for it, but in hindsight—I probably should’ve been at the club.

I'd also tell my younger self that being confident in your work is not an inherently bad thing. I feel like I lost a lot of time dismissing my wins and jumping too quickly into the next goal, but taking things a bit slower could have been cool. I feel like all these things happened so fast. Right, and you've just arrived in New York. No, literally. Sometimes, even in Santiago, I would look around my apartment and wonder, "How could I even afford all of this? How and when did all of this happen?"

I'd also tell my younger self that being confident in your work is not an inherently bad thing.

It would have been nice to allow myself to enjoy each moment a bit more. I'm trying to be more intentional about practicing that as I get older.

Could you share a list of three recommendations—you pick the topic.

I have a gazillion iPhone notes of random things I could recommend! One of my favorites is music albums. These are some my favorites lately:

Terrace Martin and Gallant's Sneek. From 2023 but I only discovered it recently. Love the little jazz bits and how modern it feels at the same time. Great for sketching, doing something chill, or just appreciating the view. I wish I could listen to it for the first time again.

47 EP by Chezile. I stumbled upon a song from this album on an IG post and immediately went looking for more—and thank god there was! Loving Chezile’s work so far and can’t wait to see what he does next.

Feel feelings by Soko. Another one I wish I could experience for the first time again. I had “Replaceable Heads” on repeat for most of last winter. 20 out of 10.

What song do you currently have on repeat in the same music theme?

La trama y el desenlace by Jorge Drexier

This is one of my favorite songs of all time, by one of my favorite artists of all time. Jorge Drexler originally studied medicine but later pivoted to his actual calling in life and became a musician in his early thirties. Since then, he’s earned 15 Latin Grammys and was the first Uruguayan to win an Oscar for one of his songs. “La Trama y el Desenlace” (“The Plot and the Unraveling”) talks about how sometimes beauty lies not in grand finales, but in the unraveling of the everyday plot.

Enjoyed the Conversation with Laura Sandoval? You can find her at

https://lausandoval.com and @laurasideral on Instagram, X, and LinkedIn.

Laura is also passionate about giving back to the New York City Dyke March.

The New York City Dyke March is a protest march where thousands of Dykes take the streets each year in celebration of beautiful and diverse Dyke lives, to highlight the presence of Dykes within our community, and in protest of the discrimination, harassment, and violence we face in schools, on the job, and in our communities. A donation was made (by west & ease and matched by Laura!) to the New York City Dyke March as part of this Conversation.

You can support the New York City Dyke March by donating directly.

I loved this so much! Leslie, as always beautiful interviewing and storytelling. Lau, what an incredible journey. I loved hearing your path to design, full of creative endeavors that impacted and influenced you as a person and a designer. New York will treat you well, so much to be curious about!

Live lauf love